Pod Talk

a communiqué for connecting all involved in the Pēpi-Pod® programme

by Stephanie Cowan

When resources are limited, evidence must guide our decisions.

Tēnā koutou

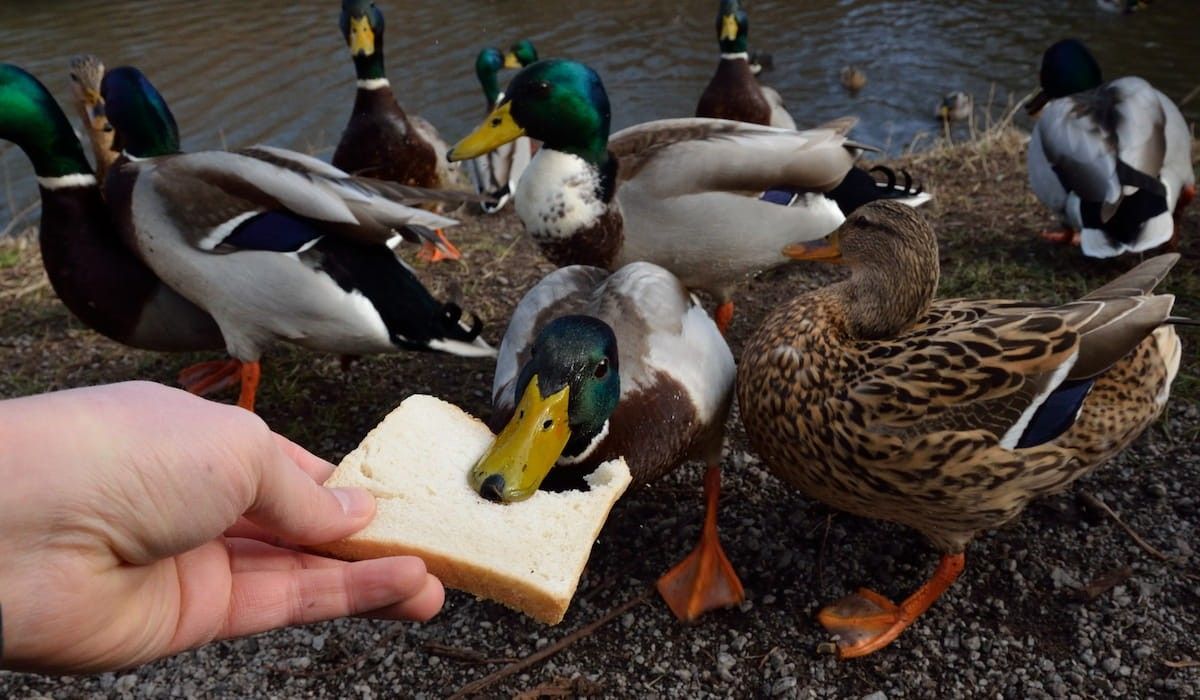

Would you feed bread to the ducks if it was your last loaf, your only piece, with hungry children waiting in line?

How would you decide who gets bread and who misses out? In this analogy, bread represents the fundamentals of life. When bread is plentiful, feeding the ducks might seem harmless, playful, kind. But when children miss out on their breakfast toast because the ducks got the last of the bread, we must ask: 'Are we making good decisions, and what responsibility takes priority when the bread is running low?' In this story, 'bread' is the in-bed sleeper: a simple, low-cost intervention that can save a baby’s life. But when there aren't enough to go around, who gets one, and who misses out?

What research is telling us

Last week, a paper was published in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health titled ‘Who is supplied with in-bed sleepers (Pēpi-Pod and wahakura) for reducing SUDI in New Zealand?’ (link) It reports that 65% of infants most in need of in-bed sleepers - those at highest SUDI risk - are missing out. Yet, enough in-bed sleepers were available for all priority babies in the study group. The paper concludes: “In-bed sleepers need to be used by high-risk infants when bed sharing, if SUDI rates are to be lowered.” This is the single most effective action we can take - based on current evidence.

A baby who missed out

This morning, I read a coroner’s report about Baby K - a young pēpi exposed to nicotine during pregnancy, who bed shared without protection, and who might still be here if a Pēpi-Pod or wahakura had been available, and used, that night. We will never know for sure, but his death is a stark reminder of what is at stake if in-bed sleepers are not prioritised to those who need them most. Baby K is not an isolated case, but now the norm in New Zealand. Most SUDI pēpi are born early, small or nicotine-exposed (tobacco or vaping), bedsharing at the time of death, less than 5 months old, and have no in-bed sleeper available.

From abundance to scarcity

The study above examined a time of relative abundance (2019–2021), when over 7,000 Pēpi-Pods and an estimated 2,000 wahakura were distributed each year. Yet even in that context of plenty, only a third reached babies with clear biological risk. In 2025 we face a different reality. Supply is half what it was during the study period - enough for only half of our priority pēpi. But even this reduced number is comparable to the early programme years (2010–2016), when infant deaths fell by 30%. Back then, we did more with less. So how do we do it again?

Facing the ethical tensions

It’s unlikely that health teams are deliberately diverting in-bed sleepers from babies at highest SUDI risk. It is likely that decisions are being shaped by competing values, assumptions, or uncertainties that unintentionally leave high-risk babies unprotected. These tensions - about vulnerability, priority and the hard calls that must be made to align our actions with evidence - may require uncomfortable conversations. However, if we are to save lives, they are conversations we must have.

Not all vulnerabilities are equal

We may be confused about what is meant by 'high risk' for SUDI as vulnerability comes in many forms - social, environmental, biological. And not all vulnerabilities carry the same SUDI risk. In-bed sleepers were designed for pēpi with biological vulnerability - those born small, early or nicotine-exposed. Vulnerable on the inside. These pēpi are at highest risk for SUDI because they have reduced ability to respond to suffocation risk, and that vulnerability follows them into every sleep.

Yes, in-bed sleepers may offer value to whānau in terms of convenience, cultural relevance, peace of mind or where there is hardship. But when these benefits are prioritized over the protection of biologically-vulnerable babies, we lose sight of the core purpose of in-bed sleepers.

Compassion guided by evidence

It may feel deeply unfair to withhold an in-bed sleeper from a struggling young mama with no safe place for her pēpi - especially when accessing other supports like a cot or bassinet can be difficult. That feeling is compassion. We care. And it is also compassion to reserve in-bed sleepers for babies who need them most, because unlike traditional infant beds, only in-bed sleepers reduce the dangerously high SUDI risk caused by smoking and bedsharing. When our compassion is guided by evidence, we resolve ethical tensions and direct in-bed sleepers to where they may make the difference between life and death for a biologically-vulnerable pēpi.

What must change in 2025

We are way off course with using in-bed sleepers to reduce sudden infant death. There is an urgent need to align our decisions with the best available evidence, and do more with less as we have before. In 2025, with reduced supply, our responsibility is clearer than ever. We must prioritise biological risk for who gets in-bed sleepers, and the saving of lives as our purpose. There are two simple criteria:

- smoking in pregnancy (or vaping)

- born < 37 weeks or <2500 grams

If we do not make this shift in thinking and practice, our efforts will drift further off course, and more babies like Baby K will quietly miss out.

In memory of baby K

I dedicate this blog to Baby K and to his whānau - with deep respect for their loss, and with hope that their story will sharpen our focus. We can’t change what happened for Baby K, but we can choose differently for the babies who come next. We have the knowledge. We have the tools. We have the responsibility. This blog is a call to prioritise biological risk when deciding where we direct our diminishing supplies of Pēpi-Pod and wahakura because they are not just support, but a vital opportunity for survival.

Mā te wā, Stephanie